LITHOGRAPHY 101

Printmaking Lingo

Edition

Edition refers to the numbered impressions of a particular image that are printed after the artist has given approval to print. At Tamarind, the edition includes all numbered prints, the artist’s proofs, the bon a tirer (good to pull or approval to print) which belongs to the printer, and three impressions for the Tamarind archives, which is housed at The University of New Mexico Art Museum. All impressions, including the trial proofs, color trial proofs, and artist’s proofs, are documented.

Documentation

Tamarind established standards of documentation that are followed by fine print workshops around the world. Complete documentation is prepared for each edition, capturing all of the details related to the edition and the steps involved in its making. This documentation is signed by the artist and the printer, and is available to anyone who asks; in fact, some states have laws that require the seller to provide specific information related to the edition.

Originality

A fine print is considered an original work created in the workshop by the artist. At Tamarind, the artist and the printer work in collaboration to produce a matrix that will be used to produce the edition. This matrix does not exist outside of the workshop, and the print that is pulled from it is considered an original work. The idea of the print being produced in multiples is inherent in the process, but does not mean that the work is a reproduction. An important consideration of originality is the degree to which the artist has participated in the concept and execution of the image.

Curator

At Tamarind, the curator is the individual who examines each print in the edition for printing quality and consistency, and documents every aspect of the edition. If printing flaws are detected, the curator either makes repairs or destroys the print. After inspecting the edition, the curator numbers, chops, defines, and oversees the signing of each new edition. The curator ensures that Tamarind’s established standards of quality, documentation, and care are maintained.

Workshop or Printers Chop

Identifying symbols of the print studio and/or the printer that are often embossed in the paper (or they may be stamped in ink on the back of the print).

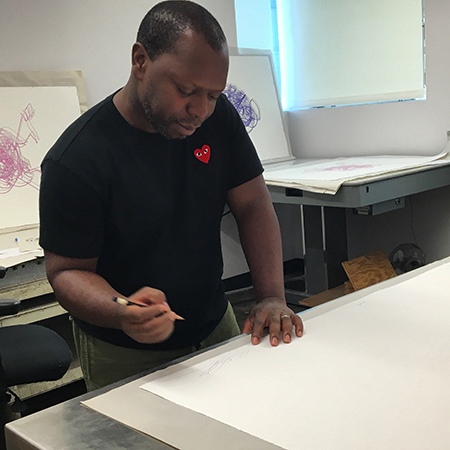

Collaborative Printmaking

Collaborative printmaking is encouraged at Tamarind, bringing artist and printer together in the workshop for a creative exchange of ideas and technical possibilities. The printer brings technical expertise and an understanding of how the process might be best handled to achieve the results the artist is seeking. Frequently the creative exchange sparks new developments for both the artist and the printer.

Lithography is one of the most direct printmaking techniques, and has the appearance of being as immediate as drawing on paper. Unlike woodcut and intaglio, lithography is a chemical medium, based on the principle that oil and water don’t mix. The artist draws with a greasy material–using anything from chalk or crayon to liquid tusche applied with a brush–on to a prepared matrix of either limestone or an aluminum plate. Once the drawing is completed, the printer stabilizes the image for printing. The printer first sprinkles rosin on the surface to protect the drawing, then applies talc to the surface, which helps the chemical etch to lie more closely to the greasy particles of the drawing. The matrix is treated with a chemical solution consisting of gum arabic and nitric acid, known as an “etch”, that helps to bond the greasy drawing material to the surface. The stone or plate is then wiped down with a solvent to dissolve most of the drawing materials, leaving only a ghost version. The barely visible drawing is now able to accept the printing inks, and the moistened areas that are blank are able to reject the printing inks. The stone or plate is moistened with water, with the printer “sponging” throughout the printing process. An oil-based printing ink is applied with a roller, adhering only to the positive parts of the image, while being repelled by the wet areas. A sheet of paper is placed on top of the inked matrix and then run through the press. The pressure from the press transfers the image to the paper.

Lithography was invented in 1798 by Aloys Senefelder in Munich, apparently by accident. Of the printmaking techniques, lithography has the most thoroughly documented history.

Process

First an artist draws an image, in reverse, on a fine-grained limestone or an aluminum plate.

For a one-color lithograph, this will be the only drawing. Each additional color will generally require a separate drawing on a different stone or plate.

Artists use the same kinds of tools they would to make images on paper or canvas. However, since the basic principle of the hand lithographic printing is the natural repulsion of grease and water, the crayons, pencils, and washes used in lithography have a high grease content.

Once the artist has finished drawing with the greasy black pigments, the printer takes over and chemically treats the stones and/or plates to stabilize the image for printing.

The printer first sprinkles rosin on the surface to protect the drawing, then applies talc, which helps the chemical etch lie more closely to the tiny grease dots that compose the drawing.

A solution of gum arabic and nitric acid (called an “etch”) is applied to the stone

…and left for about an hour to combine with the greasy particles and the calcium carbonate of the limestone. Often a second application of gum arabic is applied before the original drawing materials are removed with a solvent and asphaltum is rubbed in.

This process causes the image area, now barely visible on the stone, to accept the printing inks, and, at the same time, causes the stone’s blank areas, when moistened with water, to reject the inks.

At the press, the printer sponges the stone or plate with water to keep the surface damp.

An oil-based printing ink is applied with a roller, adhering only to the positive parts of the image, while being repelled by the wet areas.

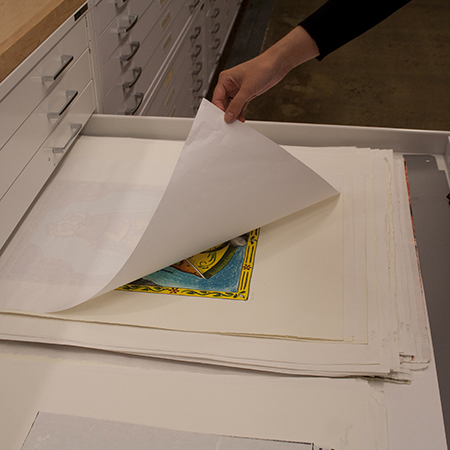

Multi-color print registration, and putting the paper through the press

In a multi-color print, the printer must ensure that the colors hit in exactly the correct place as the paper passes through the press many times. This process requires exact registration for each run. The printer makes tiny pencil marks on each sheet of paper to be printed and lines them up to correspond with marks on each stone or plate.

Once properly registered, the tympan is lowered. A tympan is a polycarbonte, flexible sheet which provides a smooth glide surface between the scraper bar of the press, and the paper. The printer then lowers the scraper bar, and the press bed is cranked through the distance of the print.

A final proof is signed by the artist as the bon a tirer ("good to pull").

The printer continues to make proofs with different color and paper combinations until the artist is completely satisfied with the result. This final proof signed by the artist becomes the standard for the printer. From this proof, the printer prints the full edition, comprised of a limited number of individual impressions.

A printer pulls the edition

Edition refers to all impressions of a particular image that are printed after the artist has given an approval to a print. At Tamarind, the edition includes all numbered prints, the artist’s proofs, the bon a tirer, which belongs to the printer, and three impressions for the Tamarind archives, which is housed at the University of New Mexico Art Museum. All impressions, including the trial proofs, color trial proofs, and artist’s proofs, are documented.

Now it's time for Tamarind's curator to get involved

At Tamarind, uniformity among impressions is assured because the curator checks each impression against the bon a tirer. Only those impressions meeting Tamarind’s high standards are embossed with the identifying symbols, called chops, of the workshop and the printer; any flawed impressions are destroyed.

“Chops” are identifying symbols of the print studio and/or the printer that are often embossed in the paper ( or they may be stamped in ink on the back of the sheet). They are important identifying marks, but not all original, limited-edition prints will have them. Artists who print their own work may not use them.

The artist signs and numbers each impression to indicate his or her approval.

Signatures and numbers usually appear on the front, but occasionally the artist chooses to sign on the back. Usually there are two numbers separated by a slanted line-for example, 5/20. The bottom number tells you how many impressions there are in the numbered edition; the top number is the designation for that impression.

Framing and proper print storage

N Ask for references for framers from knowledgeable friends, print dealers, or museums. Since improper framing can permanently damage your print, it’s important to find a professional framer who uses archival materials.

IS IT NECESSARY TO HAVE A MAT AROUND MY PRINT?

A window mat is a matter of personal taste. Often a print with a border is simply hinged to a backing -this is called “floating” the print-and requires a spacer, hidden by the edges of the frame, to keep the print from touching the glass in the same way that a window mat does. A window mat may cover the edges of the paper if you prefer (although the edges are considered to be an integral part of the print) or the print may float within the window.

YOU MENTIONED HINGES: WHAT DO YOU MEAN?

Prints are never glued or taped directly to a backing with pressure-sensitive tapes; hinges made of linen or fine Japanese paper hold the print to the backing with non-acidic, non-staining, reversible adhesives.

WHY SHOULDN’T MY PRINT TOUCH THE GLASS?

Both glass and acrylic sheeting (plexiglass) condense moisture from the air; if your print touches either, it may actually stick to the surface and be ruined.

WHICH IS BETTER-GLASS OR PLEXIGLASS?

Both will protect your print and filter some of the harmful rays of light. Glass is less expensive, but it breaks easily. Ultraviolet filtering glass and plexiglass are available at a higher cost. Since glass is heavier than plastic, it may be impractical for very large prints. Plexiglass, although lighter, is more expensive than ordinary glass, scratches easily, and carries an electrostatic charge that causes it to attract dust. Sometimes this charge can even cause drawing materials such as charcoal and pastels to crumble.

HOW CAN LIGHT HURT MY PRINT?

Bright daylight, and even bright artificial light, can cause colors to fade and papers to discolor and become brittle. Too much light is harmful even when ultraviolet rays are filtered out, so make sure your print is exposed only to moderate light for limited hours at a time. You might also consider rotating your prints from time to time.

WHAT IF I WANT TO STORE MY PRINTS?

When handling unframed prints, make sure you work with gloves or very clean hands. Finer smudges, dirt, or dents and tears caused by carelessness will affect the value of your print. If you must handle your print, lift if by diagonally opposite corners to avoid creasing. Prints should be stored flat, either in or out of archival mats, layered between sheets of non-acidic interleafing tissue. ever store your prints against surfaces such as corrugated board or wood; not only are the materials acidic, they also have textures that can imprint themselves on your artwork. Needless to say, your storage area should be clean, dry, and protected from insects and vermin. Roaches, silverfish, and mice are common despoilers of paper. Simple, relatively inexpensive non-acidic boxes will protect your prints from environmental damage; they are available from art and preservation suppliers.

Tamarind Techniques – Resources for Printers

This series of step-by-step videos, created by Tamarind Master Printer and Education Director, Brandon Gunn, is intended to help anyone who is working in a lithography workshop.

Still have questions?

This brochure was compiled by Tamarind Institute to explain the process, as well as provide valuable information on framing, storing, and caring for your lithgographs.